12 Months, 12 Languages: My Journey with the #12in23 Challenge - Mindshifting May with Prolog

Learning new programming languages is an important aspect of a software developer’s journey. It helps you expand your knowledge, learn new techniques, and approach problems in unique ways. That’s why, even in the fifth month, the #12in23 Challenge is still such an exciting endeavor for me. This month I’m focusing on Prolog to hopefully “shift” my mind into thinking about different ways I can tackle the challenges that come with software development.

If you’re not familiar with the #12in23 Challenge, it’s a programming-language learning challenge that tasks you with trying out 12 different languages in the year of 2023. It’s coordinated by Exercism.org.

The idea is simple: each month, you’ll focus on learning a new programming language. We’ll provide resources and support to help you along the way, and you can track your progress and connect with other participants on our online community.

I’m documenting my experience with this challenge throughout the year.

Each month has a specific theme in mind. For May, the theme is Mindshifting May. The focus is on languages that are quite different from mainstream languages. You can work toward the goal by completing exercises from Ballerina, Pharo, Prolog, Red, Tcl, and Unison.

I struggled to decide which language I wanted to use this Month. There are so many great options and they all excel at different things. I had to think about what I wanted to get out of this month. Ultimately, I figured the most important thing for me would be experiencing a language that makes me think about problems in ways I haven’t before. The more I researched the languages, the more I became interested in logical reasoning. So…

I chose Prolog!

Prolog stands for “Programming in Logic.” It works great for applications that can be expressed as a set of logical rules. It makes heavy use of pattern matching to search through large databases for information. Indeed, it is used in some machine learning and language modeling applications. One thing that I found particularly interesting was that Prolog “backtracks” to find multiple solutions to a problem and select the best one. It’s something I haven’t seen anywhere else and sets Prolog in a class of its own in my mind. In Prolog, you use a strongly-defined set of rules to come to some conclusion that can be applied to huge datasets, making it a great match for integrating with databases.

This time again, I’ll be installing and setting up a local development environment for this specific language. The main reason for doing this is so I can have access to more powerful developer tooling. I want it to be as easy as possible to write code, debug it, run tests faster, and just get a better sense of the real-world experience developers might have with the language in general.

Hello, World!

Exercism tracks always start with a required “Hello, World!” exercise just to make sure you can complete and submit everything okay. They gave me this code to start with.

hello_world('Goodbye, Mars!').As usual, this one was incredibly simple. I just had to make the program return “Hello, World!” instead of “Goodbye, Mars!” so I just had to change that one string.

hello_world('Hello, World!').With Hello, World! out of the way, let’s get started solving 5 exercises so we can complete this month’s challenge.

I’ll be tackling each of the 5 “featured exercises.” These exercises are chosen by Exercism because they particularly highlight a scenario where this month’s language theme is beneficial. While you can complete the monthly challenge by completing any 5 exercises, you will get an extra-special “year-long” #12in23 badge for completing the featured exercises.

The 5 exercises that exemplify mindshifting languages are Acronym, Isogram, Roman Numerals, Raindrops, and Space Age. Let’s start working on those.

Acronym

For this challenge, you must convert a phrase to its acronym. For example, Portable Network Graphics should be converted to PNG. There are a few other smaller rules that you will have to discover by reading and trying the included tests.

My solution uses Perl-compatible regular expression matching, which is loaded

from a separate module. First, I use a regex to strip the given sentence of any

unwanted characters. Then, I split the sentence into words. Then, I map over the

words and get the first letter of each. Getting the first letter is done with a

separate function which uses string_chars/2. Finally, I join the list together

and convert it to all uppercase to get the final result.

:- use_module(library(pcre)).

abbreviate(Sentence, Acronym) :-

re_replace("[^a-zA-Z0-9\s-]"/g, "", Sentence, CleanSentence),

split_string(CleanSentence, " -", " -", Words),

maplist(first_letter, Words, FirstLetters),

string_chars(LowercaseAcronym, FirstLetters),

string_upper(LowercaseAcronym, Acronym).

first_letter(Word, FirstLetter) :-

% Bind the head (first letter) of the list (word) and drop the rest

string_chars(Word, [FirstLetter|_]).Isogram

In this exercise, we must determine whether a given word is an isogram, meaning it has no repeating letters.

I again use Perl-compatible regular expression matching, so I load that module. I convert the word to uppercse, strip any non-alphabetic characters, split the word into its constituent letters, and then check if that split list is a set. A set is a proper list without duplicates, so this gives us our final result: a true or false based on if the word is an isogram.

:- use_module(library(pcre)).

isogram(Word) :-

string_upper(Word, UppercaseWord),

re_replace("[^A-Z]"/g, "", UppercaseWord, CleanWord),

string_chars(CleanWord, Letters),

is_set(Letters).Roman Numerals

From the description, this exercise seems easy: convert a number to its Roman numeral representation. This one truly embodied the spirit of “mindshifting.” I had to approach it from a way different angle than I normally do with other programming languages.

First, I created a collection of facts that map Roman numerals to regular numbers. Then, I used Definite Clause Grammar (which was a new concept to me). The DCG function I wrote uses recursion to work on the input number until it reaches the base case of 0. Each time the recursive predicate is called, I look up the Roman numeral that is less than or equal to the number. I output that numeral and subtract the difference between that numeral and the current number before recursively calling the DCG predicate again.

I use that DCG predicate inside the main predicate, calling it will phrase/2,

then converting the resulting list to strings. Finally, I use a cut ! to

prevent looking for more roman numerals after the correct one has been

generated.

roman_numeral("M", 1000).

roman_numeral("CM", 900).

roman_numeral("D", 500).

roman_numeral("CD", 400).

roman_numeral("C", 100).

roman_numeral("XC", 90).

roman_numeral("L", 50).

roman_numeral("XL", 40).

roman_numeral("X", 10).

roman_numeral("IX", 9).

roman_numeral("V", 5).

roman_numeral("IV", 4).

roman_numeral("I", 1).

convert_dcg(0) --> "".

convert_dcg(N) -->

{ roman_numeral(Roman, LargestN), N >= LargestN },

Roman,

{ NextN is N - LargestN },

convert_dcg(NextN).

convert(N, Numeral) :-

phrase(convert_dcg(N), Numerals),

string_chars(Numeral, Numerals),

!.Raindrops

This exercise has us using a set of rules to convert a number to a string of “raindrop sounds” such as “pling” and “plang.” The rules are relatively unimportant, but you can find them in the actual exercise description.

My solution uses 3 variables called Pling, Plang, and Plong that store the

strings "Pling", "Plang", and "Plong" (or empty "")depending on some

math to determine factors of the given number.

Then, if all 3 are empty, I return the number as a string according to the rules. If instead, at least one of the variables is not empty, I concatenate them all together and return that string.

convert(N, Sounds) :-

(N mod 3 =:= 0 -> Pling = "Pling" ; Pling = ""),

(N mod 5 =:= 0 -> Plang = "Plang" ; Plang = ""),

(N mod 7 =:= 0 -> Plong = "Plong" ; Plong = ""),

(Pling = "" , Plang = "" , Plong = "" ->

atom_string(N, Sounds) ;

string_concat(Pling, Plang, TmpSounds),

string_concat(TmpSounds, Plong, Sounds)

).Space Age

I’ve completed this exercise in other languages in the past (specifically Haskell). It is one of my favorites. You are given an age (in seconds) and you must calculate how old (in years) a person would be on a given planet.

Not only do I like the exercise, but I also like the solution I came to.

First, I create a collection of facts that relate the planet to its orbital period (the frequency it revolves around the sun) relative to Earth. Then in the main predicate, I get the value of that orbital period. Finally, I set the years to the given age divided by the product of the orbital period and 31557600 (Earth’s orbital period in seconds).

orbital_period("Mercury", 0.2408467).

orbital_period("Venus", 0.61519726).

orbital_period("Earth", 1.0).

orbital_period("Mars", 1.8808158).

orbital_period("Jupiter", 11.862615).

orbital_period("Saturn", 29.447498).

orbital_period("Uranus", 84.016846).

orbital_period("Neptune", 164.79132).

space_age(Planet, AgeSec, Years) :-

orbital_period(Planet, OrbitalPeriod),

Years is AgeSec / (OrbitalPeriod * 31557600).Five months down

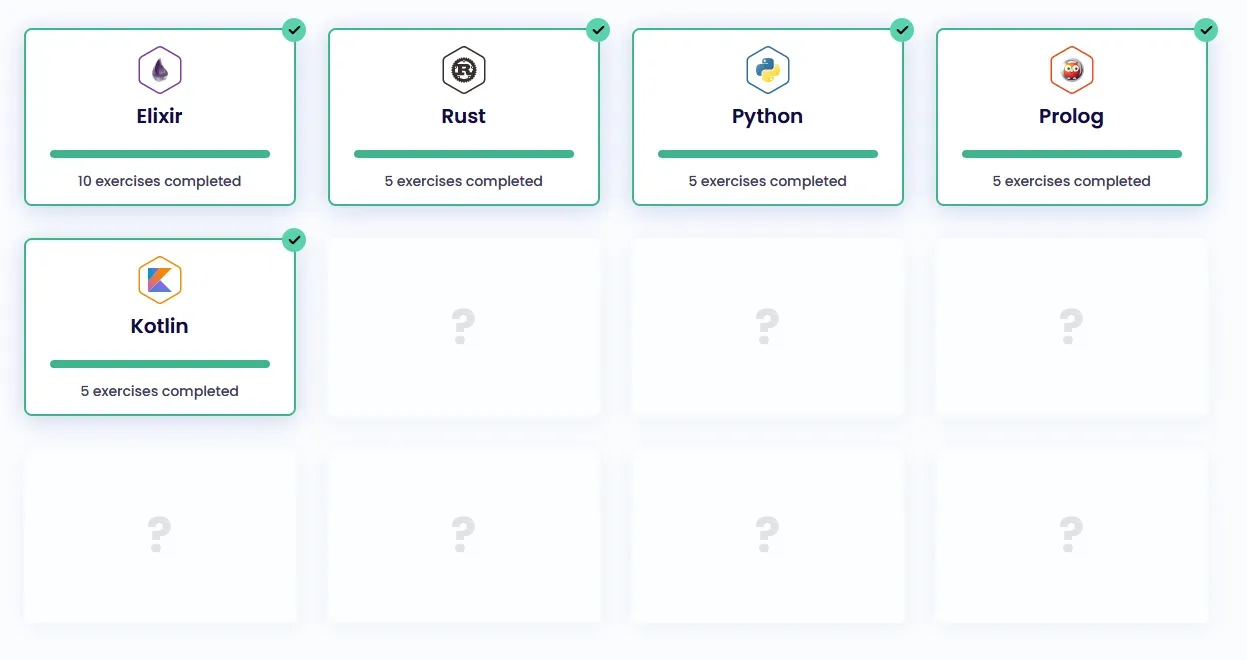

With those five exercises in Prolog complete, I’m finished with Mindshifting May! Seven more months and seven more languages to go.

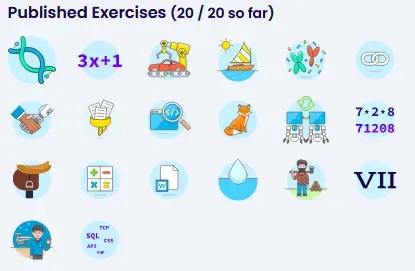

In addition, I’ve published solutions to all 20 of the featured exercises so far. This progress brings me closer to the exclusive year-long #12in23 badge.

As stated earlier, my main goal this month was to gain some insight on problem-solving; coming at problems from another angle. I can say with certainty that, while it was a challenging language, I learned new techniques and new ways to approach logical reasoning when programming. After trying Prolog, consider my mind “shifted.” Which I suppose is the whole point of Mindshifting May.

I’ve posted the solutions to this article on GitHub with much more detailed comments in the code: travishorn/prolog-exercism.

But I highly suggest you try to solve some of the exercises on Exercism.org on your own. Won’t you join me in trying 12 new programming languages in 2023? I’m curious to hear about your experience with this challenge. Leave a comment and let me know what strategies have worked for you or which languages you’re most excited to learn.

Travis Horn

Travis Horn