Conquering the #12in23 Challenge: Tackling Mechanical March with Rust

My excitement about this month in the #12in23 Challenge can be summed up in one word: Rust. Did you know Rust holds the title of the most-loved programming language by developers for 7 years in a row? More on that later.

If you’re not familiar with the #12in23 Challenge, it’s a programming-language learning challenge that tasks you with trying out 12 different languages in the year of 2023. It’s coordinated by Exercism.org.

The idea is simple: each month, you’ll focus on learning a new programming language. We’ll provide resources and support to help you along the way, and you can track your progress and connect with other participants on our online community.

I’m documenting my experience with this challenge throughout the year.

Each month has a specific theme in mind. For March, the theme is Mechanical March. The focus is on languages that compile to machine code. You can work toward the goal by completing exercises from C, C++, D, Go, Nim, Rust, V, or Zig.

I chose Rust!

Follow along as I conquer Mechanical March’s featured challenges with Rust.

Rust has held the title of most-loved language in the Stack Overflow Developer Survey for 7 years in a row now. Why do developers love it so much?

- It is memory safe with an ownership/borrowing system that prevents common programming pitfalls

- It is fast due to its strict control over memory allocations

- It supports threads and async programming so you can take advantage of modern hardware

- It uses a very expressive syntax with a powerful type system. This way you don’t have to sacrifice legibility for complexity

- It hosts a vibrant and supportive community

It’s time for me to see what Rust is all about.

As I mentioned in Functional February’s post, I’m keen to install and set up a local development environment for each language going forward. The main reason for doing this is so I can have access to more powerful developer tooling. I want writing code and debugging it to be as easy as possible. Other advantages include being able to run tests faster and just getting a better sense of the real-world experience you might have with the language in general.

Hello, World!

Exercism tracks always start with a required “Hello, World!” exercise just to make sure you can complete and submit everything okay. They gave me this code to start with.

pub fn hello() -> &'static str {

"Goodbye, Mars!"

}This one was incredibly simple. I just had to make the program return “Hello, World!” instead of “Goodbye, Mars!” so I just had to change that one string.

With Hello, World! out of the way, let’s get started solving 5 exercises so we can complete this month’s challenge.

Something new Exercism added since last month was the concept of “featured exercises.” Each month, there will be 5 featured exercises that particularly highlight a scenario where that month’s language theme is beneficial.

While you can complete the monthly challenge by completing any 5 exercises, you will get an extra-special “year-long” #12in23 badge for completing the featured exercises.

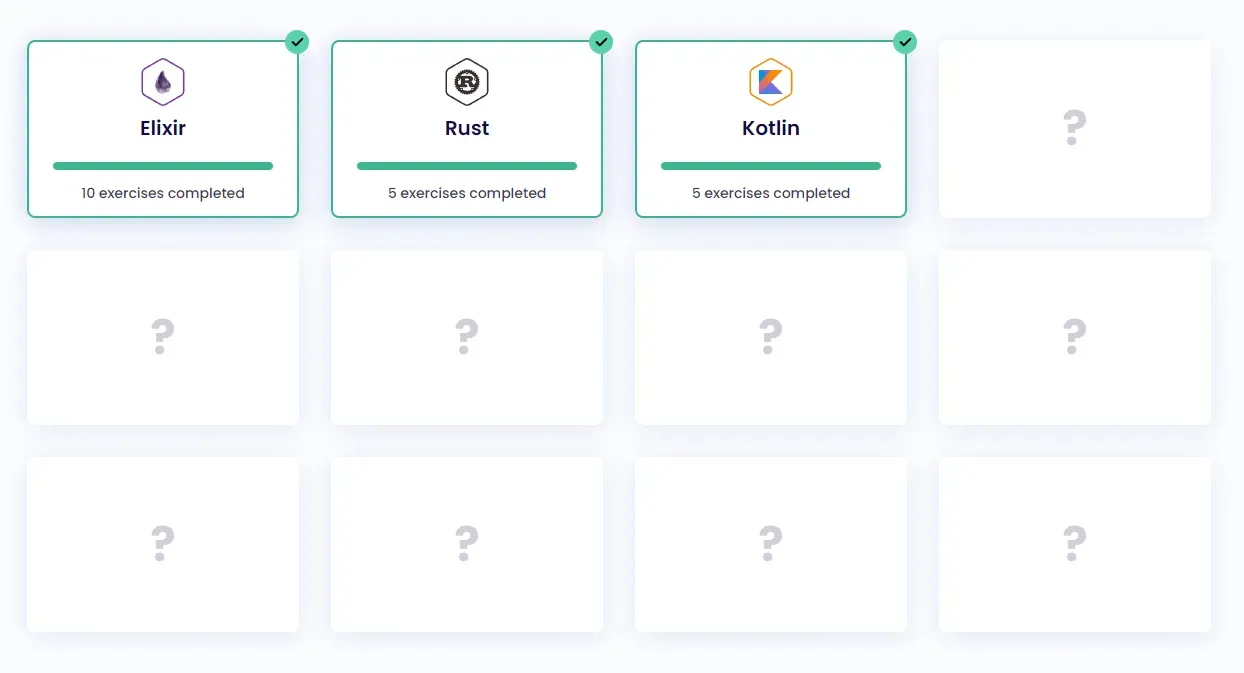

Note: The featured exercises for Functional February were chosen after I already completed 5 other exercises. I’m aiming for that “year-long” badge so I went back into the Elixir track and did Hamming, Collatz Conjecture, Robot Simulator, Yacht, and Protein Translation, as well.

The 5 exercises that exemplify Mechanical March languages are (Simple) Linked List, Secret Handshake, Pangram, Sieve, and Binary Search. Let’s start working on those.

Simple Linked List

If you already know what a linked list is, this exercise doesn’t need much explanation. You must write a simple linked list implementation that uses Elements and a List.

If you don’t know what a linked list is, you’ll need some further clarification. In short, a linked list is a list of elements. Each element contains some data and a “next” field that points to the next element in the list.

Exercism got us started with the “bones” of the code:

use std::iter::FromIterator;

pub struct SimpleLinkedList<T> {

dummy: ::std::marker::PhantomData<T>,

}

impl<T> SimpleLinkedList<T> {

pub fn new() -> Self {

unimplemented!()

}

pub fn is_empty(&self) -> bool {

unimplemented!()

}

pub fn len(&self) -> usize {

unimplemented!()

}

pub fn push(&mut self, _element: T) {

unimplemented!()

}

pub fn pop(&mut self) -> Option<T> {

unimplemented!()

}

pub fn peek(&self) -> Option<&T> {

unimplemented!()

}

#[must_use]

pub fn rev(self) -> SimpleLinkedList<T> {

unimplemented!()

}

}

impl<T> FromIterator<T> for SimpleLinkedList<T> {

fn from_iter<I: IntoIterator<Item = T>>(_iter: I) -> Self {

unimplemented!()

}

}

impl<T> From<SimpleLinkedList<T>> for Vec<T> {

fn from(mut _linked_list: SimpleLinkedList<T>) -> Vec<T> {

unimplemented!()

}

}As you can see, this isn’t going to be a simple one-liner. You need to implement functions for creating a new list, checking if a list is empty, getting the length of the list, pushing elements into the list, popping elements out of the list, peeking at the list, reversing the list, and creating a list from an iterator, as well as implementing trait to create a list from a vector.

The first thing I did was copy & paste the SimpleLinkedList struct that the

instructions gave me as a starting point.

pub struct SimpleLinkedList<T> {

head: Option<Box<Node<T>>>,

}The head property there refers to a Node struct that isn’t defined, yet. So

let’s define what a new node would look like. I knew what the (crazy-looking)

signature of the next property was because it should be the same as the head

of SimpleLinkedList.

struct Node<T> {

value: T,

next: Option<Box<Node<T>>>,

}To create a new list, I return a SimpleLinkedList instance where the head is

None. None is a little like a null value, but there are significant

differences that I’ll get to later.

pub fn new() -> Self {

SimpleLinkedList { head: None }

}When I first started to implement is_empty() I thought about iterating through

the list, counting the items, and then returning true if the count was 0. But

then I realized that we already know if the list is empty if the head is None

without needing to iterate through the list.

pub fn is_empty(&self) -> bool {

self.head.is_none()

}For determining the length of the list, however, we will need to iterate through the list.

pub fn len(&self) -> usize {

let mut current_node = &self.head;

let mut count = 0;

while let Some(node) = current_node {

current_node = &node.next;

count += 1;

}

count

}Starting with the head of the list and a count of 0, I use a while loop to

iterate through the list, updating the current node to be the next of the

actual current node and incrementing the count.

Now to push a node into the list. This got a little confusing.

pub fn push(&mut self, element: T) {

let new_node = Box::new(Node {

value: element,

next: self.head.take(),

});

self.head = Some(new_node);

}The basic idea is to create a new Node. This new node’s next points to the

current list’s head. Then we update the list’s head to be the new node,

effectively pushing the new node into the front of the list.

You’ll notice we don’t create a new Node directly. head and next items have

to be of type Option<Box<Node<T>>> remember? Since our list’s size is unknown

at compile time, it must allocate memory on the “heap”. Box is a pointer type

that allows this.

I’ll be honest. Coming from garbage-collected languages, I’m not 100% comfortable with my understanding of this stuff, but I feel I understand it well enough to at least finish these exercises.

Now we can push nodes into the list. How about popping them out of it?

pub fn pop(&mut self) -> Option<T> {

if let Some(head) = self.head.take() {

self.head = head.next;

return Some(head.value);

}

None

}First, we use Some() to make sure the head is not None. Then we update the

head to be the current head’s next, effectively removing (popping) the current

head out of the list. Then we return the current head’s value, wrapped in

Some() . It must be wrapped this way because our return type is Option,

which needs to either be None or a value wrapped in Some(). The return type

must be Option because, if the head is empty, the list is empty, there’s

nothing to pop, and we must return None.

Peek is a way to see the head value without removing it.

pub fn peek(&self) -> Option<&T> {

self.head.as_ref().map(|node| &node.value)

}Remember that head is an Option<Box<T>> type. We use as_ref() to convert

it to a Option<&T> type by taking a reference to the value inside the box.

Once we have that reference, we can’t return it directly because we want the

value of the head node, not the node itself. So we use map to get just the

value property.

Now we need a way to reverse the list.

pub fn rev(self) -> SimpleLinkedList<T> {

let mut new_list = SimpleLinkedList::new();

let mut cur_node = self.head;

while let Some(node) = cur_node {

new_list.push(node.value);

cur_node = node.next;

}

new_list

}We start by creating a new, empty list. Then we set cur_node to the original

list’s head. Next, we loop over the original list and push each node into the

new list. When the loop is finished, we just return the new list as it contains

all the original nodes, but in reverse order since they were read from last-in.

That’s all the list functions. Now we need a way to create a list from an iterator.

impl<T> FromIterator<T> for SimpleLinkedList<T> {

fn from_iter<I: IntoIterator<Item = T>>(iter: I) -> Self {

let mut list = SimpleLinkedList::new();

for item in iter {

list.push(item);

}

list

}

}Again, we create a new, empty list. Then we loop over the values in the iterator

using a for loop, and simply push in each item.

Finally, we have to create a trait that enables the creation of vectors from lists.

impl<T> From<SimpleLinkedList<T>> for Vec<T> {

fn from(mut linked_list: SimpleLinkedList<T>) -> Vec<T> {

let mut vec = Vec::new();

while let Some(node) = linked_list.pop() {

vec.push(node);

}

vec.reverse();

vec

}

}We start by creating a new, empty Vec. Then we use a while loop to iterator

over the list, popping nodes out of it and pushing them into the vector. At the

end, we reverse the vector because the nodes were popped out in reverse order.

Wow, that was a lot for one exercise. But that is kinda the point of exercising.

Secret Handshake

For this exercise, we must implement a function that accepts a decimal number and converts it to a sequence of events for a “secret handshake.” The possible events are described in binary.

00001 = wink

00010 = double blink

00100 = close your eyes

01000 = jump

10000 = Reverse the order of the operations in the secret handshake.So 19 in decimal would be 1011 in binary. There is a 1 in the position for wink,

double blink, and reverse. So the correct result would be ["double blink", "wink"].

To me, this solution was rather easy compared to Simple Linked List.

pub fn actions(n: u8) -> Vec<&'static str> {

// {:0>5b} converts to binary and pads with 5 0s on the left

let binary_string = format!("{:0>5b}", n);

// Create a new vector called result

let mut result = Vec::new();

// If character 5 is 1, push "wink" to the result

if binary_string.chars().nth(4) == Some('1') {

result.push("wink");

}

// If character 4 is 1, push "double blink" to the result

if binary_string.chars().nth(3) == Some('1') {

result.push("double blink");

}

// If character 3 is 1, push "close your eyes" to the result

if binary_string.chars().nth(2) == Some('1') {

result.push("close your eyes");

}

// If character 2 is 1, push "jump" to the result

if binary_string.chars().nth(1) == Some('1') {

result.push("jump");

}

// If character 5 is 1, reverse the result

if binary_string.chars().nth(0) == Some('1') {

result.reverse();

}

result

}We convert the decimal to binary, create a new vector, then push events into the vector if their corresponding character is 1. For 5th character (the one at index 0), don’t push anything, but reverse the sequence instead.

Pangram

For this exercise, we must implement a function that accepts a sentence and returns true or false depending on whether that sentence uses all 26 letters of the English alphabet.

This one was fun. I could do it all with one chain of methods.

/// Determine whether a sentence is a pangram.

pub fn is_pangram(sentence: &str) -> bool {

sentence

// Convert the given sentence to lowercase

.to_lowercase()

// Split the sentence into an iterator over its characters

.chars()

// Filter so that only lowercase ASCII letters remain

.filter(|c| c.is_ascii_lowercase())

// Fold the iterator into an array

// The initial array is 26 instances of `false`

.fold([false; 26], |mut acc, c| {

// Convert the letter into its ASCII value (a = 97, b = 98, etc)

// Subtract 97 from that. (a = 0, b = 1, etc)

// Use that value as an index and set to true

acc[c as usize - 97] = true;

// Return the accumulator array

acc

})

// Convert the array of true/false values into an iterator

.iter()

// Check if all values are true

.all(|&b| b)

}Sieve

This is an implementation of the Sieve of Eratosthenes. Given a number, return all the prime numbers up to that number. The tricky part is that you cannot use division or modulo.

Instead, what you must do is start at 2 and repeat a simple algorithm:

- Mark all multiples of that number as not-prime (remember, no multiple of another number can be prime)

- Go to the next unmarked (prime) number

pub fn primes_up_to(upper_bound: u64) -> Vec<u64> {

// Create a vector of booleans up the the upper bound + 1

// All values initially true. All nums are prime until marked otherwise

let mut is_prime = vec![true; (upper_bound + 1) as usize];

// Mark 0 and 1 as not prime

is_prime[0] = false;

is_prime[1] = false;

// Starting at the first prime number, 2

let mut current = 2;

// Loop while current num squared is less or equal to the upper bound

while current * current <= upper_bound {

// If the current number has not yet been marked as "not prime"...

if is_prime[current as usize] {

// Marking its multiples as not prime

// Start with the current number squared

// All previous multiples would have already been removed in

// previous iterations of the loop

let mut multiple = current * current;

// While the multiple is in bounds...

while multiple <= upper_bound {

// Set the value that represents it in the vector to false

// marking it "not prime"

is_prime[multiple as usize] = false;

// Go to the next multiple and continue checking

multiple += current;

}

}

// Go to next num in the vec to mark multiples of *it* as "not prime"

current += 1;

}

// We are left with a vector full of booleans

// true = prime; false = not prime

// Create a vector of prime numbers using this information

// Initialize a new vector

let mut primes = Vec::new();

// Iterate over all numbers from 2 to the upper bound

for n in 2..=upper_bound {

// If boolean representation of this number is true...

if is_prime[n as usize] {

// The number is prime. Push it into our `primes` vector

primes.push(n);

}

}

// Return the vector of primes

primes

}I always like these math-centered problems. They demonstrate to my programmer brain how mathematics works in the real world.

Binary Search

Implementing a binary search algorithm is a classic programming exercise. If you’re not sure what a binary search is, it’s a way to find the index of an element in a sorted list. Instead of starting at the beginning of a list and looking at values in order, a binary search looks at the item in the middle of the list, compares it to the search term, then repeats the search on the left half of the list if the middle value is too high or on the right half if the middle value is too low.

The find() function we have to write looks like this.

pub fn find(array: &[i32], key: i32) -> Option<usize> {

unimplemented!();

}To implement my solution, I need this function to accept a third argument that indicates where in the original array we’re starting from. Rust does not support default arguments, so I’ll use a helper function.

pub fn find(array: &[i32], key: i32) -> Option<usize> {

find_helper(array, key, 0)

}

fn find_helper(array: &[i32], key: i32, start: usize) -> Option<usize> {

unimplemented!();

}The rest of my solution is inside this find_helper() helper function.

fn find_helper(array: &[i32], key: i32, start: usize) -> Option<usize> {

if array.len() == 0 {

return None

}

let middle = array.len() / 2;

if array[middle] == key {

return Some(start + middle);

}

if array[middle] < key {

return find_helper(&array[(middle + 1)..], key, start + middle + 1);

}

if array[middle] > key {

return find_helper(&array[..middle], key, start);

}

None

}If the given array is empty, the search key cannot be found, so we return early

with None.

Otherwise, we get the middle of the array by doing array.len() / 2.

Note: Since this is doing integer division, it always truncates numbers after the decimal place. So if the array is 5 items long, 5 / 2 = 2.5, but the .5 gets truncated and we’re left with 2.

If the value at the middle of the array is equal to the key, we found our answer! We’ll add the index we were looking at plus the starting position that we were told we were starting from.

If the value at the middle of the array is less than the key, we need to

recursively call find_helper(), but only pass in the right half of the array

this time. We also tell it where in the array this sub-array starts from.

If the value at the middle of the array is greater than the key, we need to

recursively call find_helper(), but only pass in the left half of the array

this time. Again, we tell it where in the array this sub-array starts from.

Finally, if none of those conditions are met (although I think one of them

always should), we return None just to make sure.

Three months down

With those five exercises in Rust complete, I’m finished with Mechanical March! Nine more months and nine more languages to go.

In addition, I’ve published solutions to all 10 of the featured exercises so far. This progress brings me closer to the exclusive year-long #12in23 badge.

Rust was my favorite of the three that I’ve done so far, although Elixir isn’t too far behind. Finding information online, reading questions & answers, and scanning through documentation for Rust was very easy. It seems that happy developers make for friendly answers and delightful documentation.

Some of the biggest pain points for me were…

- trying to understand memory management

- the incredibly strict typing system

- overwhelming error messages

Luckily, all the things that seem difficult for me as a beginner with this language actually seem like they’ll be positives as I become more comfortable with the language.

- Thinking about ownership and borrowing to ensure memory management doesn’t come naturally to me right now, but it forces you to code in a way that prevents many runtime errors you wouldn’t catch in other languages.

- A strict compiler ensures code quality and safety. I feel like I can write code faster in other languages, but if that code is low quality and breaks all the time, what good is it?

- While complex error messages are hard to parse for a newbie, it’s a blessing to have such detailed and informative messages for someone who’s building a complex application

One thing’s for sure: I’ll be keeping the Rust compiler and Rust Analyzer (the LSP used by IDEs) installed on my development machine. This is certainly not the last time I use Rust.

I’ve posted the solutions in this article on GitHub with much more detailed comments in the code: travishorn/rust-exercism.

But I highly suggest you try to solve some of the exercises on Exercism.org on your own. Won’t you join me in trying 12 new programming languages in 2023? I’m curious to hear your experience with this challenge. Leave a comment and let me know what strategies have worked for you or which languages you’re most excited to learn.

Travis Horn

Travis Horn