Exploring the Power and Beauty of Common Lisp during the #12in23 Programming Challenge

This month marks the halfway point in the yearlong challenge. This time, I ventured into the realm of Common Lisp, the renowned Lisp dialect celebrated for its expressive capabilities and rich programming heritage. Intrigued by its reputation for enabling elegant and efficient solutions, I dedicated this month to immersing myself in the language and tackling challenging exercises.

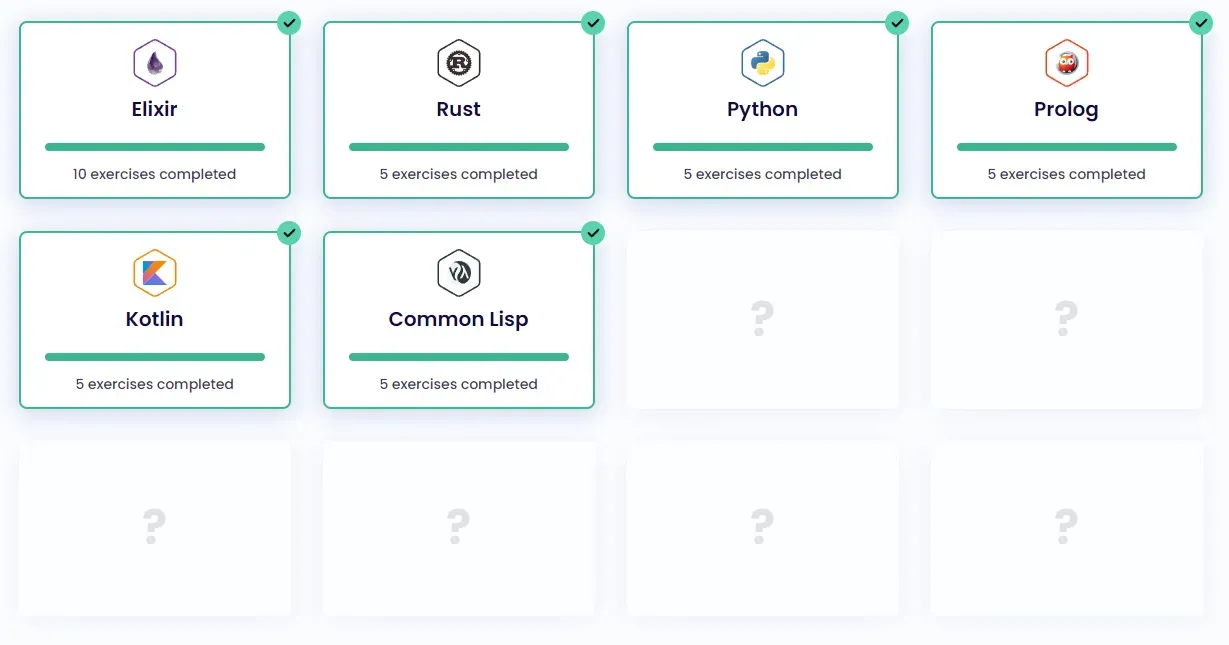

If you’re not familiar with the #12in23 Challenge, it’s a programming-language learning challenge that tasks you with trying out 12 different languages in the year of 2023. It’s coordinated by Exercism.org.

The idea is simple: each month, you’ll focus on learning a new programming language. We’ll provide resources and support to help you along the way, and you can track your progress and connect with other participants on our online community.

I’m documenting my experience with this challenge throughout the year.

Each month has a specific theme in mind. For June, the theme is “Summer of Sexps.” The focus is on languages that are Lisp Dialects; all of them use symbolic expressions, or “sexps.” You can work toward the goal by completing exercises in Clojure, Common Lisp, Emacs Lisp, Racket, and Scheme.

All of these languages are known for their simplicity, elegance, malleability, and expressive syntax. However, one of them stands out in historical significance, flexibility, extensibility, and portability. This one also comes with a rich standard library and a wealth of community resources. For those reasons…

I chose Common Lisp!

Common Lisp holds a prominent place in the history of Lisp dialects. It is a standardized and mature language that has been widely used since its inception in the 1980s. By exploring Common Lisp, you delve into the origins of Lisp and gain insights into its evolution.

It provides a powerful and extensible environment for programming. It offers a vast array of features, including dynamic typing, macros, and the Common Lisp Object System (CLOS), which supports object-oriented programming. This flexibility allows you to shape the language according to your needs and experiment with various programming paradigms.

Finally, you can find an active and supportive community of experts and learners providing resources, tutorials, libraries, and forums to aid you in your learning journey.

Getting Common Lisp set up in Windows wasn’t too bad. I downloaded and installed the Steel Bank Common Lisp compiler (SBCL). Then I installed the Common Lisp VS Code extension by Qingpeng Li. I could then write code in VS Code with full language support.

I did my tests by…

- Opening up a terminal in VS Code (Ctrl + `)

- Launching the REPL with

sbcl - Loading the tests with

(load "hello-world-test.lisp") - Running the tests with

(hello-world-test:run-tests)

I’ll be tackling each of the 5 “featured exercises.” These exercises are chosen by Exercism because they particularly highlight a scenario where this month’s language theme is beneficial. While you can complete the monthly challenge by completing any 5 exercises, you will get an extra-special “year-long” #12in23 badge for completing the featured exercises.

The 5 exercises that exemplify the summer of sexps languages are Leap, Two-Fer, Difference of Squares, Robot Name, and Matching Brackets. Let’s start working on those.

Leap

This is a “leap year” exercise with a simple premise: Given a year, report if it is a leap year. Everyone knows that leap years occur every 4 years. All you must do is determine whether the given year is evenly divisible by 4, right? Well, there are some additional, less-known rules surrounding leap year: even if the year is evenly divisible by 4, if it is also divisible by 100, it is not a leap year. To further muddy things, it becomes a leap year again if it is also divisible by 400. These are all rules according to the Gregorian calendar.

My solution uses mod and zerop to get the modulus (remainder of division)

and check if it is zero. If the modulus of two numbers is zero, the first is

evenly divisible by the second. With this understanding, all I did was use a

series of ands, ors, and nots to control the flow via logic.

(defpackage :leap

(:use :cl)

(:export :leap-year-p))

(in-package :leap)

(defun leap-year-p (year)

(and (zerop (mod year 4))

(or (not (zerop (mod year 100)))

(zerop (mod year 400)))))See more detailed comments for each line in the source code.

Two-Fer

I found this exercise easier than most of the others I’ve done during this challenge. Given a name, return “One for [name], one for me.” If no name is given, return “One for you, one for me.” It’s simple string interpolation.

Once I figured out how to set optional arguments, check for nil values, and

interpolate strings, this one was easy!

(defpackage :two-fer

(:use :cl)

(:export :twofer))

(in-package :two-fer)

(defun twofer (&optional name)

(if name

(format nil "One for ~A, one for me." name)

"One for you, one for me."))See more detailed comments for each line in the source code.

Difference of Squares

I enjoyed this exercise. It was sourced from Project Euler, which I have been a fan of for a long time. Here we must find the difference between the square of the sum and the sum of the squares of the first N natural numbers.

I broke this solution down into several functions which I could use with each other.

First I made a function that takes a number and returns a list of all natural numbers up to that number.

Then I used that in another function which sums all natural numbers up to a given number.

Then I wrote another function that used that same original function to return a list of the squares of all natural numbers up to a given number.

With those helper functions written, I made the two important functions:

square-of-sumwhich gives the square of the sumsum-of-squareswhich gives the sum of the squares

Finally, I wrote the difference function that simply subtracts one from the

other.

(defpackage :difference-of-squares

(:use :cl)

(:export :sum-of-squares

:square-of-sum

:difference))

(in-package :difference-of-squares)

(defun first-natural-numbers (n)

(loop for i from 1 to n collect i))

(defun sum-natural-numbers (n)

(reduce #'+ (first-natural-numbers n)))

(defun square-natural-numbers (n)

(mapcar #'(lambda (x) (expt x 2)) (first-natural-numbers n)))

(defun square-of-sum (n)

(expt (sum-natural-numbers n) 2))

(defun sum-of-squares (n)

(reduce #'+ (square-natural-numbers n)))

(defun difference (n)

(- (square-of-sum n) (sum-of-squares n)))See more detailed comments for each line in the source code.

Robot Name

This one had me jump into the details of creating and managing structs. The exercise has you “creating” robots, giving them names, and changing those names.

My solution involved:

- A

robotstruct - A

random-letterfunction that returns a random uppercase English letter - A

generate-robot-namefunction that uses that function for generating a name according to the specific naming scheme - A

build-robotfunction that makes an instance of the struct with a generated name - A

robot-namefunction which returns thenameproperty of an instance - An finally, a

reset-namefunction which usessetfto update the name

(defpackage :robot-name

(:use :cl)

(:export :build-robot :robot-name :reset-name))

(in-package :robot-name)

(defstruct robot

name)

(defun random-letter ()

(let ((alphabet "ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ"))

(string (char alphabet (random (length alphabet))))))

(defun generate-robot-name ()

(concatenate 'string

(random-letter)

(random-letter)

(format nil "~3,'0d" (random 1000))))

(defun build-robot ()

(make-robot :name (generate-robot-name)))

(defun robot-name (robot)

(robot-name robot))

(defun reset-name (robot)

(setf (robot-name robot) (generate-robot-name)))See more detailed comments for each line in the source code.

Matching Brackets

Last, but not least, was the most difficult exercise for me. Given a string

containing brackets [], braces {}, parentheses (), or any combination

thereof, verify that all pairs are matched and nested correctly.

I banged my head against the wall for a while trying to figure this one out until I eventually gave in and peeked at others’ solutions. Ultimately, what I came up with was a solution that relies on a stack data structure.

This solution defines what opening and closing brackets look like. Then it

initializes a “stack.” The main portion of the function iterates over each

character in the given string. During each iteration, it checks to see if the

character is an opening bracket. If so, it pushes the character into the stack.

If it is a closing bracket, it checks the position of that character in the

closing bracket definition. It uses that position to find what the matching

opening bracket should look like. Once those things are done, it pops the first

item in the stack. That item should be the matching opening bracket. If so, it

continues the loop. Otherwise, there is a pair mismatch and it returns nil.

Finally, if we reach the end of the string and the stack is empty, that means

all brackets had a correct match and we can return true.

(defpackage :matching-brackets

(:use :cl)

(:export :pairedp))

(in-package :matching-brackets)

(defparameter *opening* '(#\[ #\( #\{))

(defparameter *closing* '(#\] #\) #\}))

(defun pairedp (value)

(let (stack)

(loop for c across value

when (member c *opening*)

do (push c stack)

when (member c *closing*)

do (let* ((pos (position c *closing*))

(expected (nth pos *opening*))

(actual (pop stack)))

(unless (eql actual expected)

(return nil)))

finally (return (null stack)))))See more detailed comments for each line in the source code.

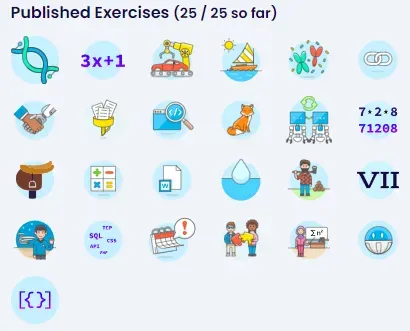

Six months down!

With those five exercises in Common Lisp complete, I’m finished with the Summer of Sexps! Six more months and six more languages to go. We’re halfway done.

In addition, I’ve published solutions to all 25 of the featured exercises so far. This progress brings me closer to the exclusive year-long #12in23 badge.

As I wrap up the challenge for this month using Common Lisp, the experience stands out as a great learning adventure. I was surprised at the expressive power and flexibility of Lisp dialects. Through solving the exercises, I gained a better appreciation of what makes them special. I’m sure that I’m a better programmer for having gained a foundational understanding of Common Lisp. I look forward to recognizing cases where Common Lisp could be helpful and implementing an elegant solution using it.

I’ve posted the solutions to this article on GitHub with much more detailed comments in the code: travishorn/common-lisp-exercism.

But I highly suggest you try to solve some of the exercises on Exercism.org on your own. Won’t you join me in trying 12 new programming languages in 2023? I’m curious to hear about your experience with this challenge. Leave a comment and let me know what strategies have worked for you or which languages you’re most excited to learn.

Travis Horn

Travis Horn